The center can hold– if you use a spindle adaptor!

In the early years of the gramophone disk, there was no standard playback speed or disc size. Berliner’s first discs were all 7-inches until the introduction of 10-inch records in 1901 and 12-inch records in 1903. The Victor Talking Machine Company began to issue 8-inch records in 1910, which were similar in size to 21-cm records popular in Europe in the first two decades of the 20th century. Playback speeds were similarly varied, from 16 RPM to 80 RPM. However, by 1915, the 10-inch, 78 RPM shellac disc became the most commonly used format.

This standard would change once again in the aftermath of World War II, which put a major dent in the music industry. Most record and phonograph makers retooled their factories for the manufacture of war-related products, but a wartime blockade also stopped the import of shellac, the material from which records were made. With the main supply cut off, the search was on for a new material for records. The synthetic material polyvinyl chloride (PVC) had been used experimentally for records since the 1930s, but at the time, it was expensive compared to shellac. However, Peter Goldmark, an engineer at Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), realized that PVC’s material properties meant that a vinyl record could be made thinner than a shellac record, and that the grooves themselves could be cut thinner, meaning that more music could fit on one side. The resulting discs held more music (and were thinner) than their shellac counterparts, recouping the costs of the more expensive material.

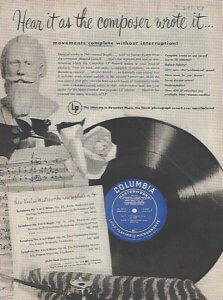

- Columbia Records LP ad, c.1945

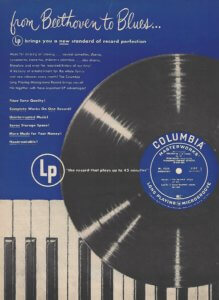

- Columbia Records LP ad, c.1945

Goldmark designed his long-playing vinyl record to play at 33⅓ RPM, and this was poised to become the new industry standard. William Paley, CBS’s chief executive, extended an invitation to RCA’s chairman, David Sarnoff, to also use this new disc format. After a private demonstration in 1948, Sarnoff was intrigued, but unwilling to join forces. In 1949, RCA unveiled its own alternative to the LP, the 7-inch 45 RPM microgroove vinyl record. Both formats had comparable sound qualities, and both strove to play long musical pieces, but they approached the problem with different technological paths . The LP could comfortably hold a movement of classical music on one side, but the 45, with its large central hole, would work better on automatic changers. Both companies heavily promoted their respective systems: CBS partnered with Philco to create an adaptor that would allow the LP to be played on any turntable, and RCA aggressively marketed inexpensive units that would play the 45 format exclusively.

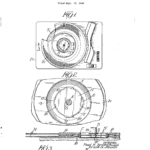

In the end, the battle of the speeds ended without a decisive winner. Manufacturers of record players began to offer multi-speed turntables that could play all three major formats. Over time, most albums were issued on LPs, and the 45 was used almost exclusively for singles, but neither format completely overshadowed the other. In 1950, RCA began to manufacture 33⅓ RPM LPs, and Columbia began to issue 45s in 1951. However, the differently sized holes did present a problem. To solve that, Paul K. Bridenbaugh and Frank A. Jansen of the Webster-Chicago Corporation created the first adaptor, a tin circle that attached to the center of the record.

In the 1949 patent application, Bridenbaugh and Jansen noted that the new vinylite records “cannot be played on phonographs designed to accommodate records with center holes of about which in the past has been standard,” but that they were flexible enough to have an adaptor inserted into their central hole without breaking, making it “possible to play disc records having the newly introduced large diameter center holes.” Alongside metal adaptors, Webster Chicago also made adaptor kits for old phonographs themselves, making it possible to play the two new speeds on older 78RPM machines, and it was there that they excelled more than in spindle adaptors. Their metal adaptors were plagued with problems, so other companies created plastic alternatives. James L. D. Morrison, for Michigan’s Voice of Music Corporation filed the first patent for a plastic adaptor, which was, he argued, “an improvement upon and has certain inherent advantages over” the metal adaptors that were, up to then, the only adaptors on the market.

Soon after, however, dozens of different plastic adaptors came on the market as more and more people bought the latest hit singles on 45s. Slightly different styles popped up, and many companies also began to manufacture these cheap contrivances to include with either records or record players. One company, which had specialized in phonograph needles but also sold adaptors by the thousands was the Duotone Corporation of Keyport, NJ, which created the adaptors we have in the Sarnoff Collection. This elegant and simple device, sold by the hundreds of thousands in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, are now all but forgotten remnants of our analog past.

Do you have an original Webster Electric metal spindle adaptor or any other early metal 45 adaptors? Consider donating them to the Sarnoff Collection, where they will be used to educate and inspire people about the history of technology for years to come. Email Sarnoff curator Florencia Pierri (pierrif@tcnj.edu) for more information.