Art, technology, and science collided in the 1960s with an innovative art collaboration between Earl Reiback and RCA

“Why has not art been affected by this all pervading influence [of television]? Perhaps quite simply, because, up until now the time was not right. Perhaps it had to await the maturing of the generation who were in their sub teens in the 1950s, those who were “brought up” on TV. They read “do it yourself” books on how to make radio and TVs. They earned pocket money repairing the neighbor’s broken sets. Or they were trained in the technology while they were in the armed forces. As in every generation, some were artists.” - Howard Wise, TV as a Creative Medium[1]

In 1969, TV as a Creative Medium opened in the Howard Wise Gallery in New York City. This seminal exhibition was the first one in the country that was dedicated solely to what later would be called video art, and inspired a new generation of artists to use television—a technology that was only 30 years old—in novel ways. It had been showing avant-garde work in the intersection of art and technology since it was founded, but after the gallery’s move from Cleveland to New York City in 1960, the Wise began to focus on works that used technology’s ability to move light in novel ways, eventually becoming one of the country’s preeminent purveyors of light art.[2] The gallery often displayed the work of people whose initial training was not in art, but the sciences—people like the industrial chemist John Healey, aeronautical engineer Frank Malina, and nuclear engineer Earl Reiback.

As a former engineer, Reiback was interested in the ways in which technology could inform artistic practices. As he explained to WNYC’s Patricia Marx before his one man show at the Wise in 1968, he used light as his creative medium, taking as his inspiration the work of Thomas Wilfred. “People haven’t yet gotten the idea that [luminal art] is art,” he explained, “because it involves light and isn’t on a canvas. People haven’t yet fully realized that this is an aesthetic unto itself.”[3] When the Wise organized Reflections, a show dedicated to technological art, Reiback knew that he wanted to push the boundaries of luminal art even further.

Reiback was fascinated with liquid crystal materials, especially their ability to control the reflection of light electronically. Scientists had known about the property of some materials to form liquid crystals since the late nineteenth century, but they became a rapidly developing focus of research at RCA in 1962, when engineers there hoped to use liquid crystals to develop flat panels that would replace the bulky cathode ray tubes of conventional televisions.[4] When Reiback wanted to incorporate this new technology in his art, he went to the group at RCA Labs working on liquid crystal displays.

In late April, 1969, Louis Zanoni, a technician in the liquid crystal group at RCA Labs in Princeton, and H.P. Kieltyka, a researcher at the LCD group in RCA’s Somerville facility, were working on mirrors. They wanted to “establish a procedure that would yield perfect 3’’ x 4’’ liquid crystal mirrors,” and after trying six different methods, they were able to create one “perfect working cell,” though that cell was plagued by bubbles on the surface of the display, which were eventually removed by a long stint in a vacuum chamber.[5] Not long after, Reiback approached RCA to ask for a liquid crystal mirror that was larger than the LCD group had ever successfully created—an 8’’ x 8’’ square divided into four equal quadrants.

Tasked to create this seemingly-impossible mirror was Zanoni and Ronald N. Friel. The two had been working together to create new applications for dynamic scattering LCDs since William Webster assumed the position of Vice President for RCA Labs in 1968. He insisted that the work undertaken at the Labs be of “increased relevance to RCA’s needs,” even if that came at the expense of “fundamental research in favor of advanced development.”[6] Even though creating a technologically advanced mirror for an art exhibit was not exactly “relevan[t] to RCA’s needs,” it would have garnered a good deal of publicity, and would have brought an emerging technology to the consciousness of the gallery-going public.

Unfortunately, the liquid crystal mirror was not a success. Zanoni and Friel first sent Reiback, as requested, an 8’’x 8’’ mirror, created using the procedure that they had perfected back in late April. This mirror was separated into four quadrants, with each section “randomly activated by a modified seven segment decoder driver” created by Zanoni and Friel. The display lasted for three days before it became inoperative, likely after the cells shorted.[7] The two men then created a second display and rushed it from the Princeton laboratory to RCA’s New York offices to be installed directly in the Wise Gallery.[8] This mirror was much like the first, but with a cell that was twice as thick. While this display did work properly, its surface was riddled with bubbles,[9] an issue that had been present even in the smaller “perfectly working cell” they had created a month before. This glass was also plagued with technical problems, not least of which was the sagging of the glass in the center of the mirror, a common difficulty in creating early liquid crystal displays.[10] That sagging resulted in localized shorts, a problem that eventually led to its removal from the show altogether.[11]

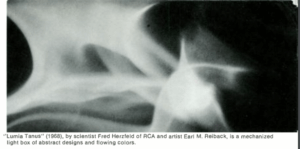

Reiback’s collaboration with RCA, disastrous as it turned out to be would not be his last. In the 1968 Some More Beginnings, a show organized by Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T), Reiback exhibited “Lumia Tanus,” a mechanized light box that used lenses and prisms, along with a computer-optimized program designed by RCA’s Fred Herzfeld that governed the movement shown on a lumia box.[12]

A few months after Reflections closed, Reiback once again worked with RCA engineers for the Wise’s new show, 1969’s TV as Creative Medium. Reiback’s contribution, Three Experiments within the TV Tube, returned to the older technology of the cathode ray tube, but used in ways that forced the viewer into new ways of seeing. Working with RCA’s Harrison tube division, he “worked within the depth of the TV tube,” as the exhibit catalog put it, to examine the relationship between CRTs and painting. In “Electron Beam,” RCA engineers created a tube without the phosphor coating on the front face, to which they added neon gas to the partial vacuum. As a result, viewers could see the flow of the scanning beam of electrons, and even manipulate them with an external magnet. In “Suspension,” he created a special screen within a screen, a phosphor coated grid which received the broadcast image, while the phosphor-coated back of the screen was excited by the backscattered electrons.

His third work was “Thrust,” which had a phosphor coated screen mounted perpendicularly to the normal viewing angle, and a psychedelic swirling pattern of phosphor coating the inside of the tube. As the electron scanning beam moved across the inner screen, it would also hit the perpendicular screen, creating shooting images in response to whatever was being broadcast.

The technological advances of the modern age allowed artists like Reiback to reconceptualize traditional media and to include movement, rather than the illusion of it. Collaborations between artists and scientists led to a flourishing in the arts and sciences, one that continues to this day.

[1] Howard Wise, “TV as a Creative Medium” exhibition program, 1969.

[2] Tina Rivers Ryan, “Wise Lights,” in Art in America, October 1, 2014.

[3] Earl Reiback interview, WNYC, February 8, 1968.

[4] Benjamin Gross, The TVs of Tomorrow: How RCA’s Flat-Screen Dreams Led to the First LCDs, (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2018).

[5] L.A. Zanoni and H.P. Kieltyka, “3’’x 4’’ mirrors,” in Liquid Crystal Displays Quarterly Progress Report, April-June 1969, Sarnoff Digital Archive, pp. 25-26.

[6] Gross, TVs of Tomorrow, pp. 122-124, quote from p. 122.

[7] L. A. Zanoni and R. N. Friel, “Art,” in Liquid Crystal Displays Quarterly Progress Report, April-June 1969, Sarnoff Digital Archive, p. 27.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] L. A. Zanoni and N. R. Goldstein, “Sagging of Soft Glass,” in Liquid Crystal Displays Quarterly Progress Report, April-June 1969, Sarnoff Digital Archive, p. 25.

[11] L. A. Zanoni and R. N. Friel, “8in x 8in Art Display,” in Liquid Crystal Displays Quarterly Progress Report, July-September 1969, Sarnoff Digital Archive, p. 27.

[12] Tom Shachtman, “Art and Technology,” in Electronic Age, Vol, 28, no. 2 (1968): 2-7.