Pigeon post inaugurates a new technology in Philadelphia

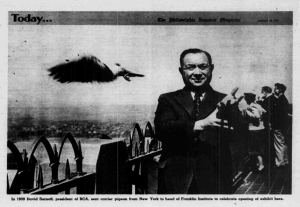

On June 5, 1939, RCA president David Sarnoff released a carrier pigeon from the RCA building at 30 Rockefeller Center in New York City. It flew up to Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute to deliver an important message for the Institute’s president, Philip Staples. As the press release from RCA’s Department of Information described it, the company wanted to send a message via a “medium more than a thousand years old” to inaugurate the dawn of a new one: television. The choice of messenger was largely symbolic, as there were of course more direct ways of communicating than pigeon post in 1939,[1] but the medium of the message was not the only symbolic touchstone—the use of the Franklin Institute for the demonstration was as well.

In August 1934, Philo Farnsworth staged the first-ever public demonstration of electronic television at the Franklin Institute, a 20-day affair where television receivers were set up in the Stearns Auditorium, and cameras filmed everything from a football game played on the Franklin’s front lawn to a cellist attempting to play while the bright television lights melted the glue that held his instrument together. Despite RCA’s triumphant start to the press release that was sent out in advance of this pigeon publicity stunt, the city in reality had gotten the first glimpse of the possibility of television five years earlier. Also, the (albeit few) people who had television sets in the area (mostly engineers who were involved in the development of the technology) could watch experimental television broadcasts from a choice of three stations: W3XE (a Philco station broadcast from north Philadelphia), W3XPF (Farnsworth’s station in Wyndmoor, PA), or W3XAD (RCA’s Camden station). Television, while still novel, was hardly new.

This Philadelphia exhibit also came not long after RCA debuted its television broadcasting capabilities (and commercially available television receivers) at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. For that demonstration, the NBC television transmitter atop the Empire State Building sent the program out from its antenna on a short radio wave, which acted as the carrier for the picture and sound. These radio waves traveled in a straight-line path, so the reception limit was the line of sight from the top of the Empire State Building. That was enough to reach the fairgrounds in Queens for the World’s Fair demonstration (and provide a brilliant strategy to advertise the RCA television sets that were available for purchase at several New York City stores) but RCA had broader aspirations for its new technology and the equipment that received it.

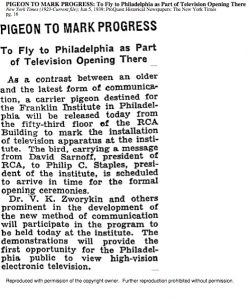

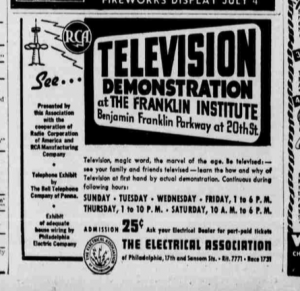

The demonstration at the Franklin Institute was smaller than that done at the RCA pavilion in the World’s Fair, but it was nevertheless very popular. The exhibit opened with remarks by RCA’s head of electronic research (and key contributor to the development of television) Vladimir Zworykin. Joining him were the heads of the Electrical League of Philadelphia, Bell Telephone Company, and the Philadelphia Electric Company. The demonstrations continued for the next two weeks, with each day drawing more and more crowds. RCA had set up the demonstration similar to what they had done in New York City: visitors were captured on television cameras as they stood in line to enter the auditorium with receivers, and saw the images of the people in line behind them on the screens.

The Franklin Institute also arranged a program of cultural events that would be televised throughout the month.[2] On one day, the Franklin televised a science lecture, and on another, the Academy of Natural Sciences presented a lecture on natural history.[3] Another day saw a televised art class run by members of the Academy of Fine Arts, where viewers learned to draw caricatures from Emidio Angelo, and watched the Academy’s paining teacher Roy Cleveland Nuse paint a portrait.[4] There was a special program with city leaders for Flag Day on June 13, an entire variety show was performed live for the camera on June 15, on June 24, Mary Lindsay and G. N. Mariano were the first couple to have a televised wedding, and police used the opportunity to televise photographs of a wanted criminal and a missing child.[5] Local businesses also joined in the fun… and in the advertising potential. The Frank & Seder department store took over a few cameras on June 10 for the world’s first televised fashion show. “Learn the secrets of this modern day miracle,” an advertisement for the show read, “be ‘televised’ yourself [and] see the highlight of the program, Frank & Seder’s fashion models both by television and in person.”[6] A week after the exhibit opened, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that more than 3,500 people attended in the first five hours it was open.[7] Variety magazine called the stunt “a showmanly demonstration,” and various newspapers called it the “marvel of the age.”[8] The more than 50,000 visitors to the Franklin Institute had caught the television bug.

While history hasn’t preserved the fate of the bird who carried the initial message, the technological innovation described in the note it carried certainly took flight.

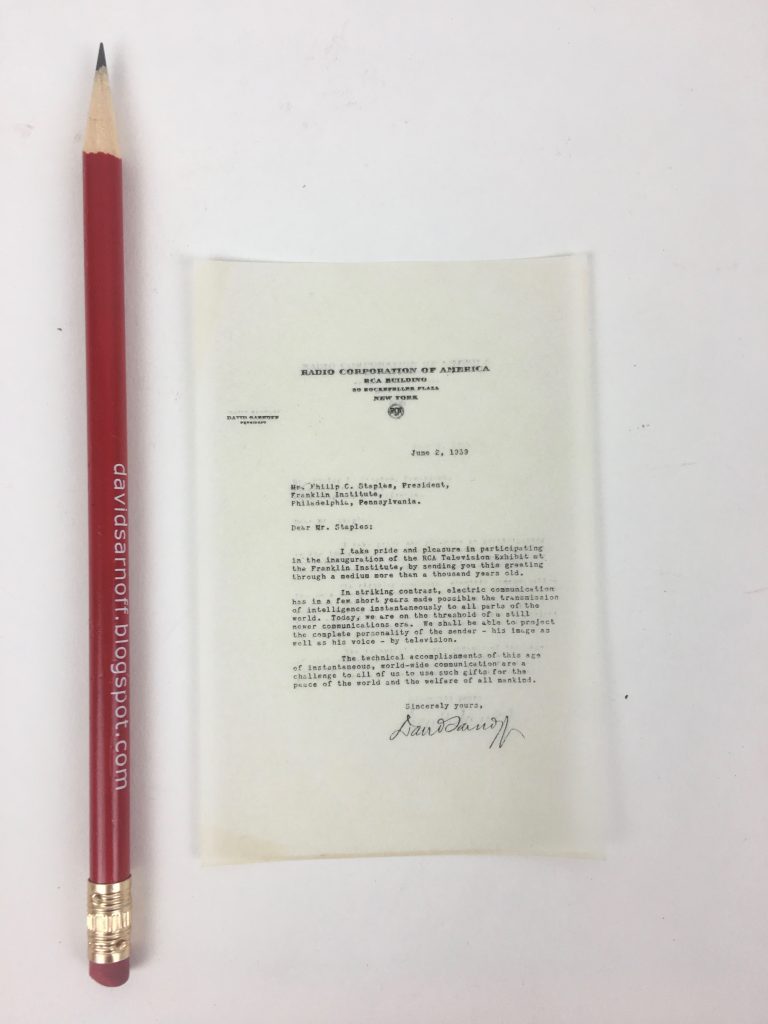

Transcript of the message:

Mr. Phillip C. Staples, President, The Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, Pa. Dear Mr. Staples, I take pride and pleasure in participating in the inauguration of the RCA Television Exhibit at the Franklin Institute, by sending you this greeting through a medium more than a thousand years old. In striking contrast, electric communication has in a few short years made possible the transmission of intelligence instantaneously to all parts of the world. Today, we are at the threshold of a still newer communications era. We shall be able to project the complete personality of the sender—his image as well as his voice—by television. The technical accomplishments of this age of instantaneous world-wide communication are a challenge to all of us to use such gifts for the peace of the world and the welfare of mankind. Sincerely Yours, [signed] David Sarnoff President, Radio Corporation of America

Text by Florencia Pierri

Works Cited

[1] However, it should be noted that pigeon post was by no means obsolete in that era. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin still employed a flock of birds to relay late-breaking news. They got their birds from Charles J. Love of the International Federation of Pigeon Fanciers, the same source that RCA used for their mobile mail carriers.

[2] RCA Press Release, June 4 [1939], The Sarnoff Collection at TCNJ, S. 325.16. The demonstration would run until July 9, Frank Rosen, “Notes,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 18, 1939, p. 15.

[3] “Franklin Institute, Philly, Stunts with Television; Big Crowds Paying 25c,”Variety, June 14, 1939, p. 34.

[4] “Philadelphia Teaches Art by Television Now,” The Christian Science Monitor, July 10, 1939, p. 4.

[5] “Plan Television of Flag,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Tuesday Morning, June 13, 1939, p. 30. “Franklin Institute, Philly, Stunts with Television; Big Crowds Paying 25c,”Variety, June 14, 1939, p. 34. Franklin Institute Shows Television to Thousands,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Friday morning, July 7, 1939, p. 30. “Mrs. Brusco Uses Television in Plea,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Sunday morning, July 2, 1939, p. 5.

[6] “Frank and Seder Givers the First Television Fashion Show,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Friday morning, June 9, 1939, p. 12.

[7] “3500 Are Televised at Franklin Institute,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Monday morning, June 12, 1939, p. 14.

[8] “Last Day to See Television,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Sunday morning, July 9, 1939, p. 9.