Why did it take so long for air conditioning to enter the American home? An analysis of RCA’s AC advertisements gives one suggestion.

The 1950s were an era of great technological innovation. Color TVs, computers, microwaves, and even self-driving cars, but one of the most welcome technologies to enter the American home during the summer months had to be home air conditioning. Artificial cooling, of course, was nothing new. The famously decadent third century Roman emperor Elagabalus cooled his villa in the summer with snow carted in from the mountains by a donkey, and in the nineteenth century, President James Garfield died in agony from a gunshot wound, but at least he did so in an artificially cooled room.[1] In 1902, engineer Willis Carrier invented the first modern air conditioning system, which was implemented in a printing plant, and in 1925, a smaller unit was put into Rivoli Theatre in New York City for the theater-going public to enjoy.[2] Over the next few years, the technology spread, but mostly to movie theaters, department stores, factories, and to a few offices. Home air conditioning was still a nearly unimaginable luxury. During the war years, that indulgence became even more scarce, as the War Production Board’s Order L-38 prohibited the manufacture of the installation of any equipment (like air conditioners) that were meant solely for personal comfort.[3] But, in the post-war boom, manufacturers realized that the time was ripe for the personal air conditioner to enter the home. Companies like Frigidaire and Carrier had been players in the air conditioning market since the 1910s, but others, including RCA (which decided to sell them in 1951) also flocked to sell this new commodity. [4]

https://youtu.be/M89AY_lzTpU

When RCA decided to enter the air conditioning market, they didn’t do so lightly. The company president, Frank Folsom, had long wanted RCA to be more of a player in the post-war white goods market, but a steel shortage made an all-out entry impossible.[5] Instead, the company opted to go into the industry one item at a time, starting with an air conditioning system. This decision was spurred by two issues: the first, a pronouncement by the company’s chairman David Sarnoff; and the other, simple economics. In September of 1951, Sarnoff gave a speech at RCA Labs in Princeton to commemorate his 45 year anniversary in the radio industry, and to mark the renaming of RCA Labs to The David Sarnoff Research Center. While appreciative of the present he had been given for his 45th anniversary, for his 50th, he told RCA engineers, he wanted three specific presents. One of these was an all-electronic air conditioner that would cool without the need for any moving parts. He even took the liberty of trademarking a name for this as-of-yet unrealized invention, calling it the Electronair.[6]

While the engineers could dream of all-electronic air conditioning in the labs, Folsom still wanted a product that he could sell in the here-and-now. In the end, he also decided that (mechanical) air conditioning would be the company’s first foray into the manufacture of consumer electronic devices that weren’t televisions, radios, or phonographs.[7] In making the decision, president Folsom was thinking of RCA’s bottom line. As the vice president for the RCA Victor Division, Robert A. Seidel, noted, “the home air-conditioning market has scarcely been tapped.”[8] That wasn’t an understatement— of the 39,000,000 American homes with electricity in 1951, less than one half of one percent of those had air conditioning.[9] As Seidel pointed out, the sales potential was there, but for some reason, the sales were not. If the technology had been around since 1902, why did it take so long for the air conditioner to enter the home?

Seidel lay the blame for that in the lack of installation and service facilities for air conditioning units. He argued that if consumers could draw on the existing (and ubiquitous) RCA Service Company branches to install and service air conditioners along with their televisions and radios, they would be more likely to purchase them.[10] However, once the RCA air conditioners went on the market, their list price did not include installation or a service contract, because despite Seidel’s praise of the reach of the RCA Service Company, there were plenty of electronics shops that could handle installation and service, even of air conditioners.[11]

So, if it wasn’t the repair infrastructure that kept consumers from buying themselves the cooling relief that air conditioning brought, then perhaps it was price? When they debuted their first models, RCA’s cheapest air conditioner, a one-third horsepower model called the Thirty-Three retailed for $229.50, and its most expensive one was $399.50, well within the price range of other room air conditioners of the era.[12] This was expensive, of course, but in comparison, a price schedule for RCA televisions from June, 1952 shows that the cheapest television a person could buy was a 17-inch model for $199.95, and the basic 21-inch model cost more than the cheapest air conditioning unit.[13] Air conditioners were priced in the same range as televisions because, in 1952, RCA envisioned the air conditioner to “add to the comfort and pleasure of life,” much like the television had done.[14] It didn’t hurt, of course, that, as RCA’s sales department put it, “air conditioners enjoy their greatest sales during the summer when television sales tend to slacken off,”[15] or that television’s migration to the 1950s home brought in a massive heat-creating device into American living rooms.

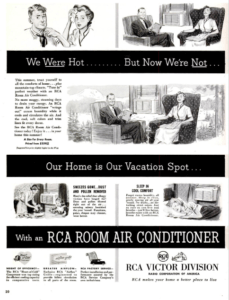

To that end, the first theme of their aggressive first advertising campaign was “tune in to perfect weather with an RCA room air conditioner.”[16] The first ad in the “Tune In” campaign appeared in Life on May 26, with subsequent ads in that magazine, newspapers, and TV spots during popular shows like Kukla, Fran and Ollie.[17] The language of these advertisements linked cool air and pleasure, and focused on the satisfaction that air conditioning brought. “This summer,” one ad read, “treat yourself.”[18] Another Life ad promised the housewife “more leisure time— less housework” with this new invention.[19] RCA, like other air conditioner manufacturers, sought to promote the idea of air conditioning as an attainable convenience, and something that belonged in the home just as much as it did in the workplace.[20] However, sales didn’t hit the expected mark, still lagging far behind those of similarly priced televisions.

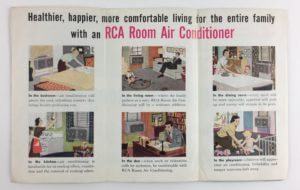

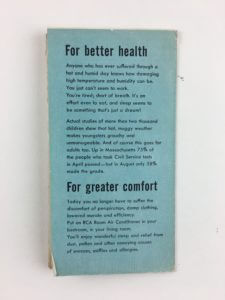

At first glance, it seems that air conditioning sales languished despite their association with luxury; however, retailers and advertisers soon began to suspect that it was because of this link that sales still did not meet up to expectations. As Gail Cooper has pointed out in Air-Conditioning America, retailers realized that postwar buyers “might view air conditioning not simply as an expendable frill but as an unjustified extravagance.”[21] In order to sell more units, therefore, retailers had to shift public perception of cool air from an extravagance to a necessity, and we see this in RCA’s advertisements, which, in subsequent campaigns, changed their focus from desire to need. Starting in 1954, they dropped the “tune in” campaign and shifted instead to a promoting the health and productivity benefits of cool air in the home. In 1954 RCA issued a promotional brochure for that year’s air conditioner models, and the rhetoric of leisure and luxury was nowhere in sight. Instead, the brochure promised that “you’ll feel better” with air conditioning, but that good feeling wasn’t one of morally suspect idleness, but of honorable efficiency. The brochure touted the benefits of cool air “for the professional man,” where an air conditioned office “promotes a sense of well being which helps to relieve strain and tension,” and “for the business man,” whose “work can be accomplished much more efficiently and expeditiously with less fatigue.”

But it wasn’t just in the workplace that cool air promoted virtue, but also in the home. If in 1952 RCA promised the housewife less housework, two years later— amidst pictures of women assiduously making the bed, cooking dinner, and setting the dinner table— it touted cool air’s effect on productivity in the home. Air conditioning, this brochure also promised, would bring “health-producing rest” and with it, “appetites will perk up and energy will remain at its peak.”[22]

The brochure’s claims veered from the patently obvious to the absurd. “Actual studies,” one of the claims actually read, “show that hot, muggy weather makes youngsters grouchy and unmanageable.” Surely the intended audience for this advertisement knew that her children (and, no doubt, she herself) were cranky in the heat, but this advertising campaign couched that irritability as detrimental to personal health and prosperity, not just the natural outcome of a hot summer. After all, the brochure reminded its readers, “[u]p in Massachusetts 75% of the people who took Civil Service tests in April passed— but in August only 58% made the grade.”[23] This statistic is largely meaningless, but the message was clear: cool your environment, increase your efficiency.

By changing the emphasis, this new campaign suggested that air conditioning wasn’t a luxury to turn your home into an oasis—it was a necessity to make sure that your family was happy, healthy, and productive. Far from being frippery, air conditioning was now virtuous. By 1955, one in twenty-two American households had air conditioning, a huge increase from previous years.[24] This trend grew exponentially over the next five years, and so did RCA’s air conditioning sales, and the units they offered. Many factors contributed to the triumph of home AC in the late 1950s: the post-war boom, growing consumerism, mass-production, cheaper prices, and even the architecture of the new suburban American home. But, none of this would have been possible without a change in consumer attitudes.

Works Cited:

[1] Salvatore Basile, Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014), 46-49.

[2] Wil Oremus, “A History of Air Conditioning,” in Slate, July 15, 2013

[3] Gail Cooper, Air Conditioning America: Engineers and the Controlled Environment, 1900-1960. (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998), 140.

[4] “RCA to Enter Air Conditioning Field,” in Radio Age, October 1951, 25-26..

[5] Joseph Csida, “RCA Appliance Plans Shaped,” in Billboard, October 6, 1951, 1. For steel shortages in the post-war era, see United States Office of Technology Assessment, Technical Options for Conservation of Metals: Case Studies of Selected Metals and Products. (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1979), 122.

[6] “An electronic air conditioner for the home that would operate with tubes, or possibly through the action of electrons on solids, and without moving parts. It should be small, noiseless, inexpensive, and should fit into any size room.” The other two inventions were a device to amplify light in the same way that a speaker amplified sound (the Maganlux) and a method of recording television’s sound and sight on a tape (the Videograph). David Sarnoff, “45 Years in Radio,” September 27, 1951.

[7] “New Line of Air Conditioners Introduced by RCA,” in Radio Age, January 1952, 25.

[8] Quoted in ibid.

[9] “Air Conditioners and Dehumidifiers Marketed by RCA,” in Radio Age, April 1952, 23.

[10] Ibid.

[11] RCA offered installation and a one-year service contract for all air conditioner purchases for $29.95, but it did not come with the list price, “Confidential RCA Air Conditioning Price Schedule,” March 5, 1952, The Sarnoff Collection, S. 645.5.

[12] “Confidential RCA Air Conditioning Price Schedule,” March 5, 1952, The Sarnoff Collection, S. 645.5; “RCA-Victor to Enter the Air Conditioning Field,” in The Pittsburgh Press, October 2, 1951, 36.

[13] $279.95 for the Lambert, the cheapest 21-inch model, “1952-1953 RCA Victor Television Price Schedule,” June 24, 1952, The Sarnoff Collection, S.645.5.

[14] “Air Conditioners and Dehumidifiers Marketed by RCA,” in Radio Age, April 1952, 23.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., 24.

[18] “We Were Hot …… But Now We’re Not……….. Our Home is Our Vacation Spot,” in Life, July 14, 1952, 20.

[19] “Just as Sure as you Live … and Breathe,” in Life, June 23, 1952, 73.

[20] Prior to 1952, approximately 80 percent of air conditioners were installed in commercial facilities

[21] Gail Cooper, Air-conditioning America: Engineers and the Controlled Environment, 1900-1960. (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 140-141. For more on the moral element to cool air, see Shane Cashman, “The Moral History of Air-Conditioning,” in The Atlantic, August 9, 2017.

[22] “You’ll Feel Better,” c. 1954, The Sarnoff Collection, S. 645.6.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Basile, Cool, 198