Happy New Year from the Sarnoff!

Friend of the Sarnoff Collection — and our December 2021 presenter — Gary Woodward has kindly allowed us to post an excerpt from The Sonic Imperative: Sound in the Age of Screens, his new book on the undervalued but crucial sonic realm. Given the richness and breadth of Gary’s inquiries and examples we found the task of choosing a relatively brief section of the book a pleasantly difficult one! Bearing in mind……this collection’s — and RCA’s, and the Sarnoff Research Institute’s — focus on sound recording, reproduction, and distribution, we’re presenting an extended passage from “Chapter 6, Capturing and Storing Sound,” where Gary places technical developments, commercial forces, cultural changes, and private — indeed, deeply personal — expression all in context with one another. Put another way, it’s not every day that a piece of writing starts out with Judy Garland and ends up with Nipper, the RCA Victor logo!

Gary is a careful scholar and his chapter footnotes — which we removed for readability — along with book purchase and free download information can be found here: https://www.sound-in-the-age-of-screens.com/. Enjoy Gary’s insights— and if you simply must read more right away check out https://theperfectresponse.pages.tcnj.edu/tag/the-sonic-imperative/ for another excerpt.

From The Sonic Imperative: Sound in the Age of Screens, by Dr. Gary C. Woodward, Professsor Emeritus, The College of New Jersey:

Songs mark a secret calendar. Their structures already save a place for what happens before it happens.

—Geoffrey O’Brien

An audible flaw in a classic recording reveals the limitations and possibilities of the medium. The year was 1961, and the problem was a relatively simple one: a single snare drum in Mort Lindsay’s backing band for Judy Garland was too loud. The drummer’s heavy hand came down harshly on the second and fourth beats of a tune she had sung for years. Drums are generally untuned timekeepers in otherwise tuned ensembles. But they still need to blend, especially when accompanying a singer.

Yet there would be no easy fix for Judy at Carnegie Hall, considered one of the great live recordings of American popular music. Back from bouts of drugs and depression, Garland sang this one performance to Manhattan’s elite gathered in the famous auditorium. There was no way to “comp” the song by assembling different takes to create a clean version. Even so, the album topped the Billboard charts for an impressive 73 weeks, flaws and all. Garland had a history with “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart.” As a 16-year-old she sang it in the film Listen Darling (1938). A year later she would be on her way to superstardom in The Wizard of Oz, made on the MGM lot where she grew up. Frank Baum’s story of a young innocent carried on the wind still plays in theaters and on television. Even in 1939 it was clear that Garland had the phrasing and vocal control of a master musician who could find her way to a song’s emotional center.

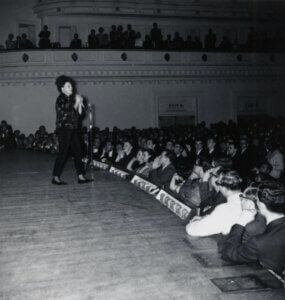

The album is a useful talisman for the problems and opportunities created with recorded sound. An audio engineer who re-mastered an updated version recalls that Capitol Records used a three-track Ampex tape machine, probably fed by five or six microphones: some on the left side of the band, a few for the right, and a microphone that Garland carried as she moved around the stage. In one of the few available photos its clear the drummer is also sitting in front of the band. That’s a problem because percussion instruments in performance are naturally loud. They are usually tamed by arranging them behind other musicians who act as involuntary but necessary human baffles. Yet, with only three tracks to work with, and with dead thuds embedded on the same piece of tape with the contributions of other band members, there was no way to correct the heavy artillery in the final mix.

Live recording now means more elaborate multitracking, where most musicians have separate microphones that can be adjusted to balance their work with others in their group. No change so clearly separates Edison’s first recording device from our modern counterparts than the development of synchronous tracks that make it possible to separate nearly every sound source in a recording. It’s now common practice to delete or add other players as a performance is built up, sometimes by “thickening” a piece with more musicians than those who first recorded it.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. An overview of the evolution of multitrack recording is a key part of the narrative in this chapter. But a related and equally important side story is how recordings entice us to linger over audio artifacts packaged as performances. Judy at Carnegie Hall is but one example of a sonic event that still remains fully accessible: an obvious feature of recorded music that encourages at least an elemental form of connoisseurship. Almost everyone curates their own music library or pays a service that will use algorithms to do it for them. With such handy access, it is easy to understand how two hours of imperfect sound captured sixty years ago still can matter to a loyal coterie who keeps the singer’s work alive. Among other reasons, the Judy Garland concert became its own marker for many trying to navigate their own cultural place. Most of us use music made by others as proxies for our personal stories. For years members of the gay community have seen Garland’s struggles against professional and personal demons as the personification of defiant survival. Captured sound can create that kind of intense feeling. A single song can create a personal arcadia that we happily come back to again and again.

The Reinvention of the Auditory Sense

The advent of recording is the key landmark in the transition to our age of auditory immersion. It was the beginning of what listening as its own rich experience could mean for non- musicians. No single innovation is created by one individual in a cultural vacuum. Several French thinkers and inventors predate Thomas Edison in conceiving of recording as a mechanical possibility. But it was the Wizard of Menlo Park who put it all together. His device changed everything.

The year was 1877. It marks the moment when the capture of sound was a breathtaking and audacious act of defiance against what seemed like the natural order. At the close of the century Americans were open to the idea that there might be ingenious ways to converse with the dead. Some fantasists were certain that the “ether” of our mostly invisible atmosphere contained the echoes of lost souls that could be heard again. It’s doubtful that Edison had any such illusions. But he gave the mystics of his day reasons to believe. Recorded sound was indeed a kind of repudiation of death. The deceased lived on through their words and music: refutations of the idea that legacies die with their makers. The printing press 400 years earlier had made it possible to carry the disembodied thoughts of writers over time and distance. But it was quite another matter to make a record of another’s “live” voice. The very breath of a person was now audible. What did immortality mean if it was possible to witness the life force of a figure long gone? Was this new world of recorded sound a part of the promise of the “renewal” of mortals, the chance to “live again” described in the Old Testament?

In a different way the coming of the phonograph was also another kind of Gutenberg moment. The relatively simple mechanics of the phonograph make it easy to miss the cultural shift it set in motion. Sound in the pre-industrial past was a second-tier sense associated with mundane speech or, more than anything else, the noise associated with living in the world’s dense cities. But it was now on a trajectory to become an instrument of emotional fulfillment. The rapid growth of relatively inexpensive recording devices meant that performances once lost to their environments could now be replicated, stored and replayed at will. To be sure, Edison well understood the more utilitarian functions of an audio recording. Dictation was an obvious application. It is less apparent he fully appreciated that his efforts had triggered an untapped source of rapture. What was obscure then is obvious now: we expect sound to be easily accessible, portable, and rendered in near-perfect accuracy. We know it is available when we need it. Edison’s cylinder was the first step in making the world fall in love with music they had never heard.

Music is our most satisfying form of mental incitement, even while it defies easy understanding. In William James’ apt phrase, it somehow “enters the mind by the back stairs,” delivering diverse effects that add up to much more than its notes and structures would suggest. Whatever its form, the new capability wallpapers our lives with sonic documents that the auditory cortex is anxious to hear. Conventional musical invention might be beyond the abilities of most to master. But this part of the brain easily connects us to the organized sound that we relish.

Early Recording

Edison’s first recording device was demonstrated during a period in American life when chaotic industrial growth contributed to economic desperation, industrial strikes and social unrest. In the “green country” of Middlesex County, New Jersey his laboratory crew of several dozen took their lead from the dour inventor. Edison worked all the time, leaving employees and his own family to make the most of his limited attention and hair- trigger irritability. The man also had little appetite for food or sleep. All the better to launch his favorite invention, the phonograph, as well as his most consequential: a practical way to produce reliable artificial light.

But the “talking machine” was to come first: an outgrowth of what Edison learned from other early experimenters, especially Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. The key insight came from the use of a flexible diaphragm in the mouthpiece. It demonstrated how a thin membrane could flex in response to sound pressure. Edison’s contribution was to embed a stylus in its center that could create a physical imprint of sound. It was a crude but consequential transducer, which is any organ or device that converts sound from one form of energy into another: in this case, acoustic energy into the movement of the stylus.

The first device was simplicity itself: a piece of foil wrapped around a heavy can-sized drum that rotated, coming in contact with a needle attached to the diaphragm near the mouthpiece. As the drum rotated at a steady speed, a worm-screw at its center slowly moved it under the stylus at a set horizontal rate. The single continuous spiral of the groove stored sound in hill-and- dale impressions in the foil. In language we still recognize, those etched impressions were “analogues”—physical facsimiles of the captured sound—and could be played back at will. “Mary Had a Little Lamb” was among the first human utterances frozen in their tracks. The device was named a “phonograph,” a melding of two Greek terms meaning “sound writing.”

The French inventor Charles Cros submitted a similar idea to the Académie des Sciences in Paris at about the same time. But Edison’s claim on creating the first functional device is real. It was built and worked as intended, even though it would fall to other innovators to make sound recordings that were inexpensive to manufacture. He called the phonograph his “baby,” perhaps because it’s a nearly perfect example of simple physics applied to a quest that was thousands of years old. The diligent patent- seeker was certain he had found the kind of innovation that would make him financially independent for the rest of his life.

A demonstration of the invention in the New York offices of Scientific American had witnesses reaching for superlatives like “wonderful” and “astonishing.”

“We have already pointed out the startling possibility of the voices of the dead being reheard through this device. . . . When it becomes possible as it doubtless will, to magnify the sound, the voices of such singers as Parepa and Titiens will not die with them, but will remain as long as the metal in which they may be embodied will last.”

The reference to now obscure Victorian singers by these early science writers made clear that they understood where the phonograph was heading. The earliest records were made acoustically, without the use of any electrical assistance. The sound was often scratchy, and the hard wax cylinders were difficult to mass produce. While Edison lost interest for a time and turned to the bigger technical challenges of electric light, he later came back to his favorite invention, working on bigger “Amberola” cylinders and flat “Diamond disc” records with improved sound. The newer discs led to frequent “tone test performances” in front of audiences who were asked to compare live singers with their newly-minted records. The recorded sound was indeed better, but still short of achieving lifelike accuracy.

The heirs to this monumental moment can still be seen in old Edison cylinders sitting around flea markets, or in their more distant cousins of newly pressed vinyl recordings manufactured for modern diehards who find more warmth in analog (versus digital) sound.

The wonder of it all impressed no one more than Edison. Not only was he astounded at how well his invention worked, but it obviously meant something special to extend a sensory capability he had partially lost. From early adulthood he was nearly deaf from either a childhood accident or physical abuse, none of his biographers seem sure. As a result, he would sometimes bite into the edge of a wooden phonograph base to ‘hear’ its music via bone conduction. Music still mattered, though his taste for simple ditties partly explains his strange dismissal of the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff (“He thumps!”) as a potential Diamond Disc artist.

Recording eventually achieved a firm foothold on the American imagination when it was re-imagined early in the new century by a German immigrant, Emile Berliner, working with a Camden, New Jersey machinist, Eldridge Johnson. They combined patents for a new type of flat disc and player that would eventually spoil Edison’s plans to fully monetize his invention. The seven-, ten-, and twelve-inch flat shellac discs of what would soon come from the Victor Talking Machine Company could be easily pressed by a single metal “master,” making copies like a waffle iron. And where the Edison stylus etched sound undulations along the bottom of the groove, Victor discs had a different pattern that placed the physical analogues along the side. In a pattern repeated many times, the media products of one company would not play on a competing system.

Edison and Victor still shared similar recording practices that were dictated by an acoustic signal path. A musician or small group would cluster tightly around a large recording horn resembling a tapered stove pipe. What sound there was would be concentrated at the narrow end with a cutting stylus rigidly attached. It converted pressure waves amplified by the horn into corresponding indentations in a single continuous groove. Edison’s better sounding “Diamond Discs” were slowly eclipsed by cheaper records of the savvier Victor, making their players initially called “gramophones” less expensive. Victor was also better at producing a wide variety of records for its players, shrewdly licensing other companies in the U.S. and elsewhere to use its patents.

The company’s headquarters could not make gramophones and records fast enough. Radio was still a few years in the future. But it was now possible to listen to sounds from performers all over the country who made their way to the Camden studios. Military bands, sentimental waltzes, “comic” monologues, Irish ballads, duets, dance bands, popular opera singers, lamentably named “coon songs” and speeches by politicians were rushed into stores. All that was happening in vaudeville, musical theater or the flamboyant rhetorical arts was coaxed on to a disc in two- or four-minute segments. What were once sounds that were mostly exclusive to the public auditorium or theater were beginning to pile up in the homes of families with cash to spare.

Victor also pulled off one of the first great examples of branding the commodity of recorded sound. Edison wisely kept his own signature script on his hardware, but not on the records of his National Phonograph Company. By contrast, Victor’s famous trademark dog “Nipper” was everywhere. The small English fox terrier painted by Francis Barraud seemed like the perfect representation of a device that was as accessible as a toy and as far-reaching as a serious vocation. With his head cocked in front of a gramophone horn as he listened to “his masters voice,” Nipper’s presence on every Victor product made even the strangest bits of music seem to be a piece of the same fabric of connectedness. To seal their dominance, Victor eventually merged in 1929 with the growing giant, the Radio Corporation of America. In current terms, RCA Victor became a vertically integrated company with plenty of audio software to go with its hardware and broadcast interests.

Even before the merger, it would be hard to imagine another turn of the century invention that gave Americans more pleasure. As Evan Eisenberg observed in his book The Recording Angel, music had “become a thing.” The most fleeting of sensory data could be owned and played at will. What once faded into nothing was now a playable artifact. It’s a cliché to say that pieces of the culture would live on: that a “performance” was not just an event in a theater. It was fast becoming an aural anchor, all the more attractive to be on call at the whim of the individual.

Captured sound extended what it meant to be alive at the end of the nineteenth century. With the telegraph, the telephone, recordings and the coming radio, a listener could be transported away from the confines of hard times and small towns with visits to the larger creative sea of performers and Tin Pan Alley hustlers.